TOPIARY

Topiary is the horticultural practice of training perennial plants by clipping the foliage and twigs of trees, shrubs and subshrubs to develop and maintain clearly defined shapes, whether geometric or fanciful. The term also refers to plants which have been shaped in this way. As an art form it is a type of living sculpture. The word derives from the Latin word for an ornamental landscape gardener, topiarius, a creator of topia or "places", a Greek word that Romans also applied to fictive indoor landscapes executed in fresco.

The plants used in topiary are evergreen, mostly woody, have small leaves or needles, produce dense foliage, and have compact and/or columnar (e.g., fastigiate) growth habits. Common species chosen for topiary include cultivars of European box (Buxus sempervirens), arborvitae (Thuja species), bay laurel (Laurus nobilis), holly (Ilex species), myrtle (Eugenia or Myrtus species), yew (Taxus species), and privet (Ligustrum species). Shaped wire cages are sometimes employed in modern topiary to guide untutored shears, but traditional topiary depends on patience and a steady hand; small-leaved ivy can be used to cover a cage and give the look of topiary in a few months. The hedge is a simple form of topiary used to create boundaries, walls or screens.

tHE ORIGIN OF tOPIARY

Castelo Branco Portugal

European topiary dates from Roman times. Pliny's Natural History and the epigram writer Martial both credit Gaius Matius Calvinus, in the circle of Julius Caesar, with introducing the first topiary to Roman gardens, and Pliny the Younger describes in a letter the elaborate figures of animals, inscriptions, cyphers and obelisks in clipped greens at his Tuscan villa (Epistle v.6, to Apollinaris). Within the atrium of a Roman house or villa, a place that had formerly been quite plain, the art of the topiarius produced a miniature landscape (topos) which might employ the art of stunting trees, also mentioned, disapprovingly, by Pliny (Historia Naturalis xii.6).

Cloud-pruning only distantly related to natural forms in Hallyeo Haesang National Park, Geoje, South Korea

History OF tOPIARY

Far Eastern topiary

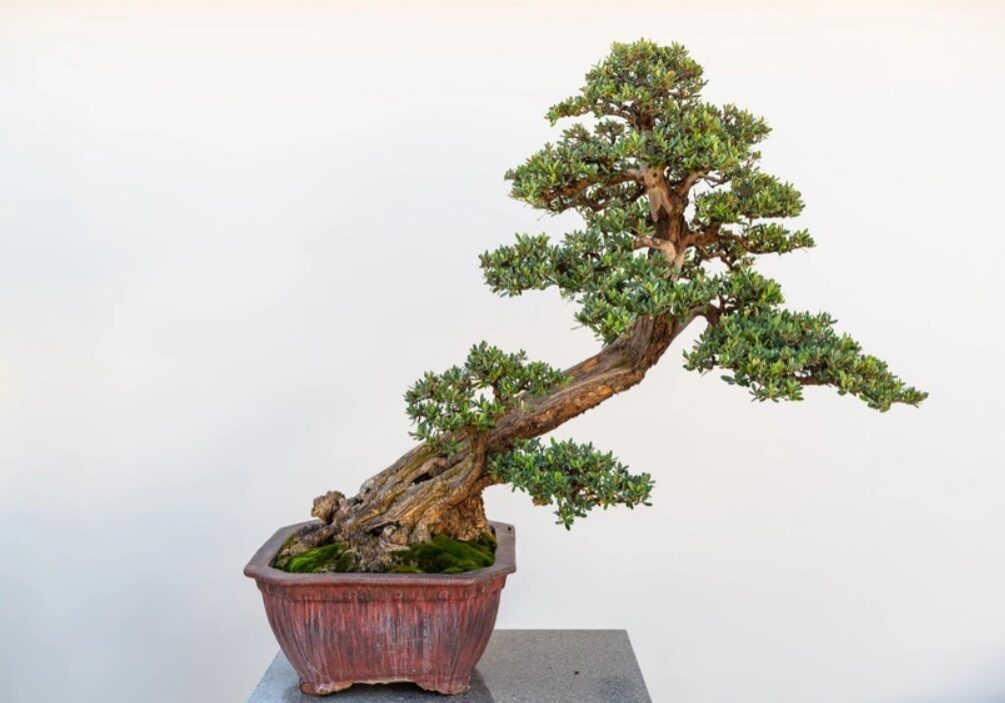

The clipping and shaping of shrubs and trees in China and Japan have been practised with equal rigor, but for different reasons. The goal is to achieve an artful expression of the "natural" form of venerably aged pines, given character by the forces of wind and weather. Their most concentrated expressions are in the related arts of Chinese penjing and Japanese bonsai.

Japanese cloud-pruning is closest to the European art: the cloud-like forms of clipped growth are designed to be best appreciated after a fall of snow. Japanese Zen gardens (karesansui, dry rock gardens) make extensive use of Karikomi (a topiary technique of clipping shrubs and trees into large curved shapes or sculptures) and Hako-zukuri (shrubs clipped into boxes and straight lines).

Simple upright topiary shapes punctuate the patterned parterres of Heidelberg ca 1590, in this view by Jacques Fouquiere.

Renaissance topiary

Since its European revival in the 16th century, topiary has been seen on the parterres and terraces of gardens of the European elite, as well as in simple cottage gardens; Barnabe Googe, about 1578, found that "women" (a signifier of a less than gentle class) were clipping rosemary "as in the fashion of a cart, a peacock, or such things as they fancy." In 1618 William Lawson suggested

Your gardener can frame your lesser wood to the shape of men armed in the field, ready to give battell: or swift-running Grey Houndes to chase the Deere, or hunt the Hare. This kind of hunting shall not wate your corne, nor much your coyne.

Traditional topiary forms use foliage pruned and/or trained into geometric shapes such as balls or cubes, obelisks, pyramids, cones, or tiered plates and tapering spirals. Representational forms depicting people, animals, and man-made objects have also been popular. The royal botanist John Parkinson found privet "so apt that no other can be like unto it, to be cut, lead, and drawn into what forme one will, either of beasts, birds, or men armed or otherwise." Evergreens have usually been the first choice for Early Modern topiary, however, with yew and boxwood leading other plants.

Topiary at Versailles and its imitators was never complicated: low hedges punctuated by potted trees trimmed as balls on standards, interrupted by obelisks at corners, provided the vertical features of flat-patterned parterre gardens. Sculptural forms were provided by stone and lead sculptures. In Holland, however, the fashion was established for more complicated topiary designs; this Franco-Dutch garden style spread to England after 1660, but by 1708-09 one searches in vain for fanciful topiary among the clipped hedges and edgings, and the standing cones and obelisks of the aristocratic and gentry English parterre gardens in Kip and Knyff's Britannia Illustrata.

In the 1720s and 1730s, the generation of Charles Bridgeman and William Kent swept the English garden clean of its hedges, mazes, and topiary. Although topiary fell from grace in aristocratic gardens, it continued to be featured in cottagers' gardens, where a single example of traditional forms, a ball, a tree trimmed to a cone in several cleanly separated tiers, meticulously clipped and perhaps topped with a topiary peacock, might be passed on as an heirloom.

Such an heirloom, but on heroic scale, was the ancient churchward yew of Harlington, west of London, immortalized in an engraved broadsheet of 1729 bearing an illustration with an enthusiastic verse encomium by its dedicated parish clerk and topiarist. formerly shaped as an obelisk on square plinth topped with a ten-foot ball surmounted by a cockerel, the Harlington Yew survives today, untonsured for the last two centuries.

It may be true, as I believe it is, that the natural form of a tree is the most beautiful possible for that tree, but it may happen that we do not want the most beautiful form, but one of our own designing, and expressive of our ingenuity

The classic statement of the British Arts and Crafts revival of topiary among roses and mixed herbaceous borders, characterised generally as "the old-fashioned garden" or the "Dutch garden" was to be found in Topiary: Garden Craftsmanship in Yew and Box by Nathaniel Lloyd (1867–1933), who had retired in middle age and taken up architectural design with the encouragement of Sir Edwin Lutyens.

Lloyd's own timber-framed manor house, Great Dixter, Sussex, remains an epitome of this stylised mix of topiary with "cottagey" plantings that was practised by Gertrude Jekyll and Edwin Lutyens in a fruitful partnership. The new gardening vocabulary incorporating topiary required little expensive restructuring: "At Lyme Park, Cheshire, the garden went from being an Italian garden to being a Dutch garden without any change actually taking place on the ground," Brent Elliot noted in 2000.

Americans in England were sensitive to the renewed charms of topiary. When William Waldorf Astor bought Hever Castle, Kent, around 1906, the moat surrounding the house precluded the addition of wings for servants, guests and the servants of guests that the Astor manner required. He accordingly built an authentically styled Tudor village to accommodate the overflow, with an "Old English Garden" including buttressed hedges and free-standing topiary. In the preceding decade, expatriate Americans led by Edwin Austin Abbey created an Anglo-American society at Broadway, Worcestershire, where topiary was one of the elements of a "Cotswold" house-and-garden style soon naturalised among upper-class Americans at home.

Topiary, which had featured in very few 18th-century American gardens, came into favour with the Colonial Revival gardens and the grand manner of the American Renaissance, 1880–1920. Interest in the revival and maintenance of historic gardens in the 20th century led to the replanting of the topiary maze at the Governor's Palace, Colonial Williamsburg, in the 1930s.

Our Topiary gardens

We have over 12 different varieties of topiary gardens to choose from and enjoy the experience of each unique and fascinating topiary, hand-crafted. You'll also get to learn the history behind each individual topiary and origin. Making your experience even more fascinating and interesting.

Drummond Castle, Scotland

Ladew Topiary Garden

Levens Hall, Cumbria, England

Longwood Gardens, Pennsylvania

Marqueyssac, Vézac, France

The topiary garden of Manor d’Eyrignac, France

Topiary Park, Columbus, Ohio

Topiary Garden

Topiary Garden

Topiary Garden

Topiary Garden

Topiary Garden

Topiary Garden

Topiary Garden

Topiary Garden

Penjing generally fall into one of three categories

Shumu penjing (樹木盆景): Tree penjing that focuses on the depiction of one or more trees and optionally other plants in a container, with the composition's dominant elements shaped by the creator through trimming, pruning, and wiring.

Shanshui penjing (山水盆景): Landscape penjing that depicts a miniature landscape by carefully selecting and shaping rocks, which are usually placed in a container in contact with water. Small live plants are placed within the composition to complete the depiction.

Shuihan penjing (水旱盆景): A water and land penjing style that effectively combines the first two, including miniature trees and optionally miniature figures and structures to portray a landscape in detail.

Chinese cultural hegemony gave the practice influence over other cultures, engendering bonsai and saikei in Japan, as well as the miniature living landscapes of hòn non bộ in Vietnam.

Curiosity

What's the difference between Bonsai and Penjing?

Generally speaking, tree penjing specimens differ from bonsai by allowing a wider range of tree shapes (more "natural-looking") and by planting them in bright-colored and creatively shaped pots. In contrast, bonsai are more simplified in shape (more "minimal" in appearance) with larger-in-proportion trunks and are planted in unobtrusive, low-sided containers with simple lines and muted colors.

While saikei depicts living landscapes in containers, like water and land penjing, it does not use miniatures to decorate the living landscape. Hòn non bộ focuses on depicting landscapes of islands and mountains, usually in contact with water and decorated with live trees and other plants. Like water and land penjing, hòn non bộ specimens can feature miniature figures, vehicles, and structures. Distinctions among these traditional forms have been blurred by some practitioners outside of Asia, as enthusiasts explore the potential of local plant and pot materials without strict adherence to traditional styling and display guidelines.

Origin of Penjing

The container known as the pen originated in Neolithic China in the Yangshao culture as an earthenware shallow dish with a foot. It was later one of the vessels manufactured in bronze for use in court ceremonies and religious rituals during the Shang dynasty and Zhou dynasty.

When foreign trade introduced into China new herbal aromatics in the 2nd century BC, a unique incense burner was designed. The boshanlu stemmed cup was topped by a perforated lid in the shape of one of the sacred mountains/islands, such as Mount Penglai – focus of a strong contemporary belief – often with the images of mythical persons and beasts throughout the hillsides. Smaller versions of the pen dish were sometimes used as bottom pieces either to catch hot embers or to be filled with water to represent the ocean out of which the sacred mountains/islands arose. Originally made out of bronze, ceramic, or talc stone, some later versions were believed to be stones which occasionally were partly covered with moss and lichens to further heighten the miniature representation.

Since at least the 1st century AD, Daoist mysticism has included the recreating of magical sites in miniature to focus and increase the properties found in the full-size sites. The various schools of Buddhism introduced from India after the mid-2nd century included the meditative dhyana sect, whose translations of Sanskrit texts sometimes used Daoist terminology to convey non-physical concepts. Also, floral altar decorations were introduced and floral designs started to become a dominant force in Chinese art. Five centuries later the Chán school of Buddhism was established, in which renewed Indian dhyana Buddhist teachings were merged with native Chinese Daoism. Chán maintained its more active, vital spirit even as other Buddhist sects were becoming more rigidly formalized.

Back to

The earliest versions

While there were legends dating from at least the 3rd and 4th centuries of Daoist persons said to have had the power to shrink whole landscapes down to small vessel size, written descriptions of miniature landscapes are not known until Tang dynasty times. As the information at that point shows a somewhat developed craft, (then called "punsai") the making of dwarfed tree landscapes had to have been taking place for a while, either in China or possibly based on a form brought in from outside.

Mural from the tomb of Prince Zhanghuai (AD 706), depicting a man with tray of pebbles and miniature fruit trees

The earliest-known graphic dates from 706 and is found in a wall mural on a corridor leading to the tomb of Prince Zhang Huai at the Qianling Mausoleum site. Excavated in 1972, the frescoes show two maid servants carrying penjing with miniature rockeries and fruit trees.

The first highly prized trees are believed to have been collected in the wild and were full of twists, knots, and deformities. These were seen as sacred, of no practical profane value for timber or other ordinary purpose. These naturally dwarfed plants were held to be endowed with special concentrated energies due to age and origin away from human influence. The viewpoint of Chán Buddhism would continue to impact the creation of miniature landscapes. Smaller and younger plants which could be collected closer to civilization but still bore a resemblance to the rugged old treasures from the mountains would also have been chosen. Horticultural techniques to increase the appearance of age by emphasizing trunk, root, and branch size, texture, and shapes would eventually be employed with these specimens.

From Tang times onward, various poets and essayists praised dwarf potted landscapes. A decorative tree guild from around 1276 is known to have supplied dwarf specimens for use in Suzhou restaurants in the province of Jiangsu.

China

Depiction of the Ming imperial court ladies tending or standing beside penjing

Since at least the 16th century, shops at the "Garden of Dragon Flowers" (Longhua) to the southwest of Shanghai, were engaged in cultivating miniature trees in containers. (These would continue to the present day.) Meanwhile, Suzhou was still considered at century's end to be the source of the finest exponents of the art of penjing.

The earliest-known English observation of penjing in China/Macau dates from 1637.

During the end of the 18th century, Yangzhou in central Jiangsu province boasted landscape penjing that contained water and soil.

Middle years

19th century

In 1806, a very old dwarf tree from Canton (now Guangzhou) was gifted to Sir Joseph Banks and eventually presented to Queen Charlotte for Her Majesty's inspection. This tree and most others seen by Westerners in southeast China probably originated at the celebrated Fa Ti gardens near Canton.

By the first half of the 19th century, according to various Western accounts, air layering was the primary propagation method for penjing, which were then generally between one and two feet in height after two to twenty years of work. Elms were the main specimens used, along with pines, junipers, cypresses, and bamboos; plums were the favored fruit trees, along with peaches and oranges. The branches could be bent and shaped using various forms of bamboo scaffolding, twisted lead strips, and iron or brass wire to hold them in place; they could also be cut, burnt, or grafted. The bark was sometimes lacerated at places or smeared with sugary substance to induce termites ("white ants") to roughen it or even to eat the similarly sweetened heartwood. Rocks with moss or lichens were also a frequent feature of these compositions.

The earliest known photograph from China which included penjing was made c.1868 by John Thomson. He was particularly delighted by the collection in the garden of the Hoi Tong Monastery on Henan Island near Guangzhou. A collection of dwarf trees and plants from China was also exhibited that year in Brooklyn, New York. In America, laws such as the Chinese Exclusion Act led to Japanese bonsai becoming more familiar to Americans. This led to the prevalence of knowledge of the Japanese forms of dwarf potted trees for the next several decades and prior to Chinese forms.

Near the end of the 19th century, the Lingnan or Cantonese school of "Clip and Grow" styling was developed at a monastery in southeast China. Fast-growing tropical trees and shrubs could be more easily and quickly shaped using these techniques.

20th-21st centuries

Established in 1954, the Longhua nursery in Shanghai included the teaching of classical theory and all aspects of the practice of penjing, a process which could take student-gardeners ten years.

As late as the early 1960s, it is reported that some 60 characteristic regional forms of penjing could be distinguished by the expert eye. A few of these forms dated back to at least the 16th century.

During the upheaval of the Cultural Revolution (May 1966-April 1969), one relatively small effect was that many collections of penjing in mainland China, especially around Beijing, were damaged or neglected because they were seen as a bourgeois pastime. After their trees were gone, some Chinese penjing masters, men in their sixties and seventies, were forced to do something considered socially redemptive—many were sent to fields to plant rice. However, in other areas of China, especially in eastern and southern China, penjing were collected for safe keeping.

Wu Yee-sun (1905–2005), third generation penjing master and grandson of a Lingnan school founder, held the first exhibition of artistic pot plants jointly with Mr. Liu Fei Yat in Hong Kong in 1968. This was a display of traditional aristocratic penjing which had survived the 1949 Chinese Communist Revolution by leaving/being protected from Mainland China. The two editions of Wu's Chinese/English book, Man Lung Garden Artistic Pot Plants, helped develop interest in this older form of what the West only knew as the later-refined Japanese art of bonsai.

The Yuk Sui Yuen Penzai Exhibition was held in Canton in 1978. This was the first public show in ten years with approximately 250 penjing from private collections displayed in a public park. Antique pots were also shown. The Shanghai Botanical Garden opened that year and permanently displays 3,000 penjing. The First National Penjing Show was held the following year in Beijing with over 1,100 exhibits from 13 provinces, towns, and autonomies.

Penjing garden at the Wuhou Shrine, Chengdu, China, 2015

One division of the Hangzhou Flower Nursery by 1981 specialized in penjing, including over fifteen hundred once abandoned older specimens being maintained and in the initial stages of being retrained. The art of penjing would again become vastly popular in China, in part due to stability returning to most people's lives and the significantly improved economic conditions; growth would be most pronounced particularly in coastal provinces of Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangdong as well as Shanghai. There would be increasing numbers of good public and private collections, the latter with anywhere from several hundred to several thousand pieces.

By the end of 1981, the China Flower and Penjing Association was formed, and seven years later the China Penjing Artists Association was likewise established.

The Hong Kong Baptist University opened the Man Lung Garden in 2000 to promote the Chinese heritage of penjing. Temporarily located on the university's Shaw Campus, in February 2005 a permanent site was set up at the Kam Shing Road Entrance of its Ho Sin Hang Campus.

Art forms of Penjing

As an art form, penjing is an extension of the garden, since it enables an artist to recreate parts of the natural landscape in miniature. Penjing is often used indoors as part of a garden's overall design, since it reiterates the landscape features found outside. Penjing pots grace pavilions, private studies or living rooms, and public buildings. They are either free-standing elements within the gardens or are placed on furniture such as a table or bookshelf. Sometimes a lattice display stand is built which adds particular prominence to the penjing specimen and exemplifies the interplay between architecture and nature.

A specimen in the landscape penjing style

Penjing seeks to capture the essence and spirit of nature through contrasts. Philosophically, it is influenced by the principles of Taoism, specifically the concept of Yin and Yang: the idea of the universe as governed by two primal forces, opposing but complementary. Some of the contrasting concepts used in penjing include portrayal of "dominance and subordination, emptiness (void) and substance, denseness and sparseness, highness and lowness, largeness and smallness, life and death, dynamics and statics, roughness and meticulousness, firmness and gentleness, lightness and darkness, straightness and curviness, verticality and horizontality, and lightness and heaviness."

Design inspiration is not limited to observation or representation of nature, but is also influenced by Chinese poetry, calligraphy, and other visual arts. Common penjing designs include evocation of dragons and the strokes of well-omened characters. At its highest level, the artistic value of penjing is on par with that of poetry, calligraphy, brush painting and garden art.

lIST OF PENJING STYLES

Anhui Style

Anhui Penjing (徽派盆景) is most famous for its utilization of ume.

Beijing Style

Beijing Penjing (京派盆景) reflects its artistic origin from the ancient traditional Chinese architecture in Beijing. The branches are often horizontal and the crowns of the trees are often in hemisphere or in the form of traditional folding fan.

Guangdong (or Lingnan) Style

Cantonese penjing (Traditional Chinese: 粵派盆景) is also called Lingnan ("South of the (Nan)ling Range") penjing (嶺南派盆景), because Guangdong is located south of the Nanling mountain range. The main characteristic of this style is its natural appeal and the appeal of easy and smooth.

Guangxi Style

Guangxi Penjing (桂派盆景) reflect the beautiful natural landscape such as that of Guilin. This style utilizes different type of stones considerably more frequent than other styles.

Fujian Style

Fujian Penjing (閩派盆景) specializes in the utilization of banyan.

Hubei Style

Hubei Penjing (湖北盆景) emphasizes on the producing the sense of dynamic feelings by the static plants and rocks, and thus also called Dynamic Penjing (动势盆景).

Jiangsu Style

Like the culinary art of the Jiangsu cuisine, the art of Jiangsu Penjing (蘇派盆景) is also complicated, with the crowns of the trees often being shaped like clouds.

Sichuan Style

Sichuan Penjing (川派盆景) tends to be well-knit, simple and unsophisticated.

Shanghai Style

Shanghai Penjing (海派盆景) has influenced the Japanese bonsai, but at the same time, has kept its original artistic origin, which is from the traditional Chinese painting.

Taiwan Style

Taiwan Penjing (臺灣盆景) is a cross of Japanese bonsai and traditional Chinese Penjing.

Xuzhou Style

Xuzhou Penjing (徐州盆景) is a branch of Jiangsu style, but it is distinct enough to be listed separately for hundreds of years for its utilization of fruit trees.

Yangzhou Style

Yangzhou Penjing (揚派盆景) is also called northern Jiangsu style (蘇北派), it is distinct from Jiangsu style The three twists of tree trunks is the most distinctive characteristic of this style.

Yunnan Style

Yunnan Penjing (雲南盆景) benefits from the extreme climatic and biodiversity of Yunnan region, between the Himalayas and the tropics. A permanent display of Yunnan style penjing is visible at Daguan Park, Kunming.

Zhejiang Style

Zhejiang Penjing (浙派盆景) specializes in utilization of pine and cypress, often have three to five plants in one tray.

Zhongzhou Style

Zhongzhou Penjing (中州盆景) specializes in utilizing Tamarix.