OUR SCULPTURES

We have over 89 different sculptures spread across various gardens, Art gallery and concert hall. Enjoy the experience of each unique artistry. You'll also get to learn the history and origin behind each individual sculpture. Making your experience even more fascinating and interesting.

What are sculptures?

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sculptural processes originally used carving (the removal of material) and modelling (the addition of material, as clay), in stone, metal, ceramics, wood and other materials but, since Modernism, there has been almost complete freedom of materials and process. A wide variety of materials may be worked by removal such as carving, assembled by welding or modelling, or moulded or cast.

Discover

Let's learn more about sculptures

Sculpture in stone survives far better than works of art in perishable materials, and often represents the majority of the surviving works (other than pottery) from ancient cultures, though conversely traditions of sculpture in wood may have vanished almost entirely. In addition, most ancient sculpture was brightly painted, and this has been lost.

Sculpture has been central in religious devotion in many cultures, and until recent centuries, large sculptures, too expensive for private individuals to create, were usually an expression of religion or politics. Those cultures whose sculptures have survived in quantities include the cultures of the ancient Mediterranean, India and China, as well as many in Central and South America and Africa.

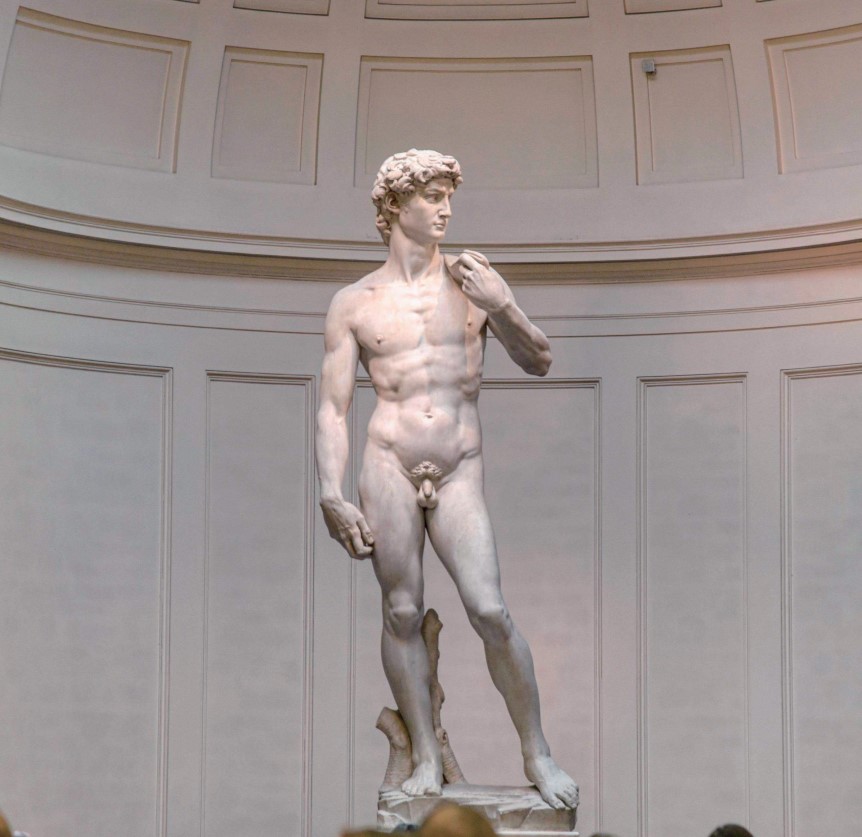

The Western tradition of sculpture began in ancient Greece, and Greece is widely seen as producing great masterpieces in the classical period. During the Middle Ages, Gothic sculpture represented the agonies and passions of the Christian faith. The revival of classical models in the Renaissance produced famous sculptures such as Michelangelo's statue of David. Modernist sculpture moved away from traditional processes and the emphasis on the depiction of the human body, with the making of constructed sculpture, and the presentation of found objects as finished artworks.

types of sculptures

Open-air Buddhist rock reliefs at the Longmen Grottoes, China

A distinction exists between sculpture "in the round", free-standing sculpture such as statues, not attached except possibly at the base to any other surface, and the various types of relief, which are at least partly attached to a background surface.

Relief is often classified by the degree of projection from the wall into low or bas-relief, high relief, and sometimes an intermediate mid-relief. Sunk-relief is a technique restricted to ancient Egypt. Relief is the usual sculptural medium for large figure groups and narrative subjects, which are difficult to accomplish in the round, and is the typical technique used both for architectural sculpture, which is attached to buildings and for small-scale sculpture decorating other objects, as in much pottery, metalwork and jewelry. Relief sculpture may also decorate steles, upright slabs, usually of stone, often also containing inscriptions.

Another basic distinction is between subtractive carving techniques, which remove material from an existing block or lump, for example of stone or wood, and modelling techniques which shape or build up the work from the material. Techniques such as casting, stamping and moulding use an intermediate matrix containing the design to produce the work; many of these allow the production of several copies.

The term "sculpture" is often used mainly to describe large works, which are sometimes called monumental sculpture, meaning either or both of sculpture that is large, or that is attached to a building. But the term properly covers many types of small works in three dimensions using the same techniques, including coins and medals, hardstone carvings, a term for small carvings in stone that can take detailed work.

The very large or "colossal" statue has had an enduring appeal since antiquity; the largest on record at 182 m (597 ft) is the 2018 Indian Statue of Unity. Another grand form of portrait sculpture is the equestrian statue of a rider on horse, which has become rare in recent decades. The smallest forms of life-size portrait sculpture are the "head", showing just that, or the bust, a representation of a person from the chest up. Small forms of sculpture include the figurine, normally a statue that is no more than 18 inches (46 cm) tall, and for reliefs the plaquette, medal or coin.

Modern and contemporary art have added a number of non-traditional forms of sculpture, including sound sculpture, light sculpture, environmental art, environmental sculpture, street art sculpture, kinetic sculpture (involving aspects of physical motion), land art, and site-specific art. Sculpture is an important form of public art. A collection of sculpture in a garden setting can be called a sculpture garden. There is also a view that buildings are a type of sculpture, with Constantin Brâncuși describing architecture as "inhabited sculpture".

Prehistoric art

The origin of Sculptures

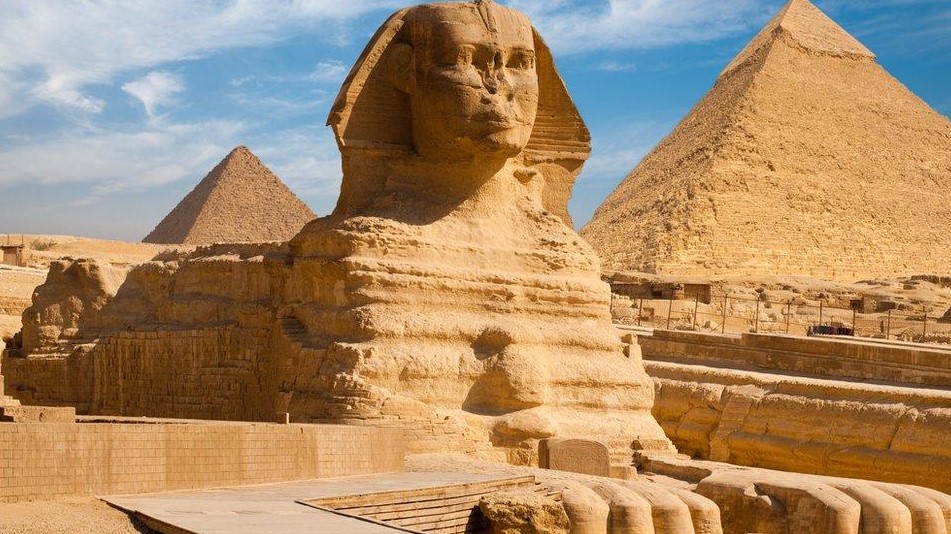

Small sculptures as personal possessions go back to the earliest prehistoric art, and the use of very large sculpture as public art, especially to impress the viewer with the power of a ruler, goes back at least to the Great Sphinx of some 4,500 years ago. In archaeology and art history the appearance, and sometimes disappearance, of large or monumental sculpture in a culture is regarded as of great significance, though tracing the emergence is often complicated by the presumed existence of sculpture in wood and other perishable materials of which no record remains;

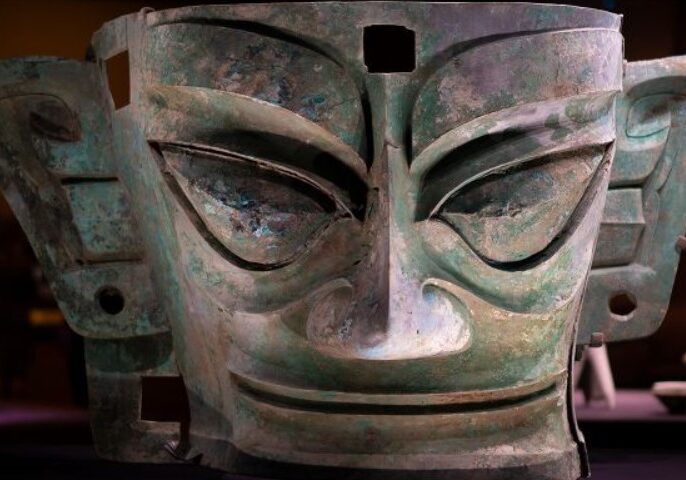

The totem pole is an example of a tradition of monumental sculpture in wood that would leave no traces for archaeology. The ability to summon the resources to create monumental sculpture, by transporting usually very heavy materials and arranging for the payment of what are usually regarded as full-time sculptors, is considered a mark of a relatively advanced culture in terms of social organization. Recent unexpected discoveries of ancient Chinese Bronze Age figures at Sanxingdui, some more than twice human size, have disturbed many ideas held about early Chinese civilization, since only much smaller bronzes were previously known.

Some undoubtedly advanced cultures, such as the Indus Valley civilization, appear to have had no monumental sculpture at all, though producing very sophisticated figurines and seals. The Mississippian culture seems to have been progressing towards its use, with small stone figures, when it collapsed. Other cultures, such as ancient Egypt and the Easter Island culture, seem to have devoted enormous resources to very large-scale monumental sculpture from a very early stage.

The collecting of sculpture, including that of earlier periods, goes back some 2,000 years in Greece, China and Mesoamerica, and many collections were available on semi-public display long before the modern museum was invented. From the 20th century the relatively restricted range of subjects found in large sculpture expanded greatly, with abstract subjects and the use or representation of any type of subject now common. Today much sculpture is made for intermittent display in galleries and museums, and the ability to transport and store the increasingly large works is a factor in their construction.

Small decorative figurines, most often in ceramics, are as popular today (though strangely neglected by modern and Contemporary art) as they were in the Rococo, or in ancient Greece when Tanagra figurines were a major industry, or in East Asian and Pre-Columbian art. Small sculpted fittings for furniture and other objects go well back into antiquity, as in the Nimrud ivories, Begram ivories and finds from the tomb of Tutankhamun.

Portrait sculpture began in Egypt, where the Narmer Palette shows a ruler of the 32nd century BCE, and Mesopotamia, where we have 27 surviving statues of Gudea, who ruled Lagash c. 2144–2124 BCE. In ancient Greece and Rome, the erection of a portrait statue in a public place was almost the highest mark of honour, and the ambition of the elite, who might also be depicted on a coin.

In other cultures such as Egypt and the Near East public statues were almost exclusively the preserve of the ruler, with other wealthy people only being portrayed in their tombs. Rulers are typically the only people given portraits in Pre-Columbian cultures, beginning with the Olmec colossal heads of about 3,000 years ago. East Asian portrait sculpture was entirely religious, with leading clergy being commemorated with statues, especially the founders of monasteries, but not rulers, or ancestors. The Mediterranean tradition revived, initially only for tomb effigies and coins, in the Middle Ages, but expanded greatly in the Renaissance, which invented new forms such as the personal portrait medal.

Animals are, with the human figure, the earliest subject for sculpture, and have always been popular, sometimes realistic, but often imaginary monsters; in China animals and monsters are almost the only traditional subjects for stone sculpture outside tombs and temples. The kingdom of plants is important only in jewellery and decorative reliefs, but these form almost all the large sculpture of Byzantine art and Islamic art, and are very important in most Eurasian traditions, where motifs such as the palmette and vine scroll have passed east and west for over two millennia.

One form of sculpture found in many prehistoric cultures around the world is specially enlarged versions of ordinary tools, weapons or vessels created in impractical precious materials, for either some form of ceremonial use or display or as offerings. Jade or other types of greenstone were used in China, Olmec Mexico, and Neolithic Europe, and in early Mesopotamia large pottery shapes were produced in stone. Bronze was used in Europe and China for large axes and blades, like the Oxborough Dirk.

Sculptures are often painted, but commonly lose their paint to time, or restorers. Many different painting techniques have been used in making sculpture, including tempera, oil painting, gilding, house paint, aerosol, enamel and sandblasting.

Many sculptors seek new ways and materials to make art. One of Pablo Picasso's most famous sculptures included bicycle parts. Alexander Calder and other modernists made spectacular use of painted steel. Since the 1960s, acrylics and other plastics have been used as well. Andy Goldsworthy makes his unusually ephemeral sculptures from almost entirely natural materials in natural settings. Some sculpture, such as ice sculpture, sand sculpture, and gas sculpture, is deliberately short-lived. Recent sculptors have used stained glass, tools, machine parts, hardware and consumer packaging to fashion their works. Sculptors sometimes use found objects, and Chinese scholar's rocks have been appreciated for many centuries.

Using materials like

stone

Stone sculpture is an ancient activity where pieces of rough natural stone are shaped by the controlled removal of stone. Owing to the permanence of the material, evidence can be found that even the earliest societies indulged in some form of stone work, though not all areas of the world have such abundance of good stone for carving as Egypt, Greece, India and most of Europe. Petroglyphs (also called rock engravings) are perhaps the earliest form: images created by removing part of a rock surface which remains in situ, by incising, pecking, carving, and abrading. Monumental sculpture covers large works, and architectural sculpture, which is attached to buildings. Hardstone carving is the carving for artistic purposes of semi-precious stones such as jade, agate, onyx, rock crystal, sard or carnelian, and a general term for an object made in this way. Alabaster or mineral gypsum is a soft mineral that is easy to carve for smaller works and still relatively durable. Engraved gems are small carved gems, including cameos, originally used as seal rings.

The copying of an original statue in stone, which was very important for ancient Greek statues, which are nearly all known from copies, was traditionally achieved by "pointing", along with more freehand methods. Pointing involved setting up a grid of string squares on a wooden frame surrounding the original, and then measuring the position on the grid and the distance between grid and statue of a series of individual points, and then using this information to carve into the block from which the copy is made.

metal

Ludwig Gies, cast iron plaquette, 8 x 9.8 cm, Refugees, 1915

Bronze and related copper alloys are the oldest and still the most popular metals for cast metal sculptures; a cast bronze sculpture is often called simply a "bronze". Common bronze alloys have the unusual and desirable property of expanding slightly just before they set, thus filling the finest details of a mould. Their strength and lack of brittleness (ductility) is an advantage when figures in action are to be created, especially when compared to various ceramic or stone materials (see marble sculpture for several examples). Gold is the softest and most precious metal, and very important in jewellery; with silver it is soft enough to be worked with hammers and other tools as well as cast; repoussé and chasing are among the techniques used in gold and silversmithing.

Casting is a group of manufacturing processes by which a liquid material (bronze, copper, glass, aluminum, iron) is (usually) poured into a mould, which contains a hollow cavity of the desired shape, and then allowed to solidify. The solid casting is then ejected or broken out to complete the process, although a final stage of "cold work" may follow on the finished cast. Casting may be used to form hot liquid metals or various materials that cold set after mixing of components (such as epoxies, concrete, plaster and clay). Casting is most often used for making complex shapes that would be otherwise difficult or uneconomical to make by other methods. The oldest surviving casting is a copper Mesopotamian frog from 3200 BCE. Specific techniques include lost-wax casting, plaster mould casting, and sand casting.

Welding is a process where different pieces of metal are fused together to create different shapes and designs. There are many different forms of welding, such as Oxy-fuel welding, Stick welding, MIG welding, and TIG welding. Oxy-fuel is probably the most common method of welding when it comes to creating steel sculptures because it is the easiest to use for shaping the steel as well as making clean and less noticeable joins of the steel. The key to Oxy-fuel welding is heating each piece of metal to be joined evenly until all are red and have a shine to them. Once that shine is on each piece, that shine will soon become a 'pool' where the metal is liquified and the welder must get the pools to join, fusing the metal. Once cooled off, the location where the pools joined are now one continuous piece of metal. Also used heavily in Oxy-fuel sculpture creation is forging. Forging is the process of heating metal to a certain point to soften it enough to be shaped into different forms. One very common example is heating the end of a steel rod and hitting the red heated tip with a hammer while on an anvil to form a point. In between hammer swings, the forger rotates the rod and gradually forms a sharpened point from the blunt end of a steel rod.

glass

Glass may be used for sculpture through a wide range of working techniques, though the use of it for large works is a recent development. It can be carved, though with considerable difficulty; the Roman Lycurgus Cup is all but unique. There are various ways of moulding glass: hot casting can be done by ladling molten glass into moulds that have been created by pressing shapes into sand, carved graphite or detailed plaster/silica moulds. Kiln casting glass involves heating chunks of glass in a kiln until they are liquid and flow into a waiting mould below it in the kiln. Hot glass can also be blown and/or hot sculpted with hand tools either as a solid mass or as part of a blown object. More recent techniques involve chiseling and bonding plate glass with polymer silicates and UV light.

Dale Chihuly (Blown glass)

pottery

Pottery and Shaping methods.

Pottery is one of the oldest materials for sculpture, as well as clay being the medium in which many sculptures cast in metal are originally modelled for casting. Sculptors often build small preliminary works called maquettes of ephemeral materials such as plaster of Paris, wax, unfired clay, or plasticine. Many cultures have produced pottery which combines a function as a vessel with a sculptural form, and small figurines have often been as popular as they are in modern Western culture. Stamps and moulds were used by most ancient civilizations, from ancient Rome and Mesopotamia to China.

wood carving

Wood carving has been extremely widely practiced, but survives much less well than the other main materials, being vulnerable to decay, insect damage, and fire. It therefore forms an important hidden element in the art history of many cultures. Outdoor wood sculpture does not last long in most parts of the world, so that we have little idea how the totem pole tradition developed. Many of the most important sculptures of China and Japan in particular are in wood, and the great majority of African sculpture and that of Oceania and other regions.

Wood is light, so suitable for masks and other sculpture intended to be carried, and can take very fine detail. It is also much easier to work than stone. It has been very often painted after carving, but the paint wears less well than the wood, and is often missing in surviving pieces. Painted wood is often technically described as "wood and polychrome". Typically a layer of gesso or plaster is applied to the wood, and then the paint is applied to that.

Soft materials

Three dimensional work incorporating unconventional materials such as cloth, fur, plastics, rubber and nylon, that can thus be stuffed, sewn, hung, draped or woven, are known as soft sculptures. Well known creators of soft sculptures include Claes Oldenburg, Yayoi Kusama, Eva Hesse, Sarah Lucas and Magdalena Abakanowicz.

Serpentine to unveil large-scale public sculpture by Yayoi Kusama

The subsequent Minoan and Mycenaean cultures developed sculpture further, under influence from Syria and elsewhere, but it is in the later Archaic period from around 650 BCE that the kouros developed. These are large standing statues of naked youths, found in temples and tombs, with the kore as the clothed female equivalent, with elaborately dressed hair; both have the "archaic smile". They seem to have served a number of functions, perhaps sometimes representing deities and sometimes the person buried in a grave, as with the Kroisos Kouros. They are clearly influenced by Egyptian and Syrian styles, but the Greek artists were much more ready to experiment within the style.

During the 6th century Greek sculpture developed rapidly, becoming more naturalistic, and with much more active and varied figure poses in narrative scenes, though still within idealized conventions. Sculptured pediments were added to temples, including the Parthenon in Athens, where the remains of the pediment of around 520 using figures in the round were fortunately used as infill for new buildings after the Persian sack in 480 BCE, and recovered from the 1880s on in fresh unweathered condition. Other significant remains of architectural sculpture come from Paestum in Italy, Corfu, Delphi and the Temple of Aphaea in Aegina (much now in Munich). Most Greek sculpture originally included at least some colour; the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek Museum in Copenhagen, Denmark, has done extensive research and recreation of the original colours.

next period is

Classical

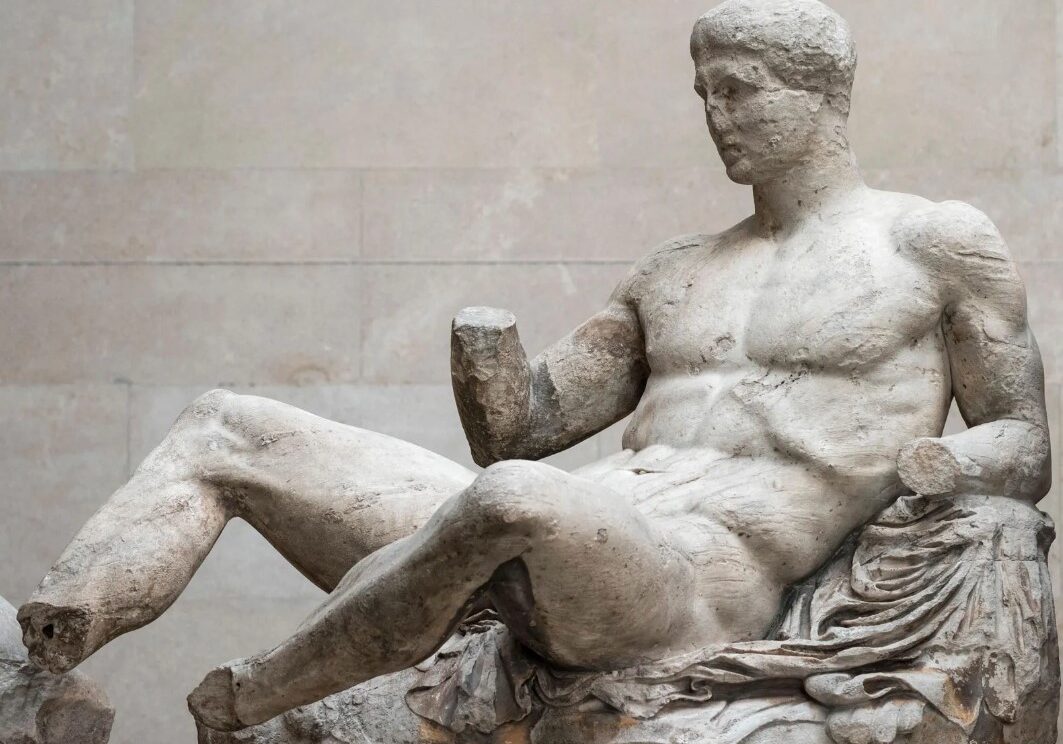

High Classical high relief from the Elgin Marbles, which originally decorated the Parthenon, c. 447–433 BCE

There are fewer original remains from the first phase of the Classical period, often called the Severe style; free-standing statues were now mostly made in bronze, which always had value as scrap. The Severe style lasted from around 500 in reliefs, and soon after 480 in statues, to about 450. The relatively rigid poses of figures relaxed, and asymmetrical turning positions and oblique views became common, and deliberately sought. This was combined with a better understanding of anatomy and the harmonious structure of sculpted figures, and the pursuit of naturalistic representation as an aim, which had not been present before. Excavations at the Temple of Zeus, Olympia since 1829 have revealed the largest group of remains, from about 460, of which many are in the Louvre.

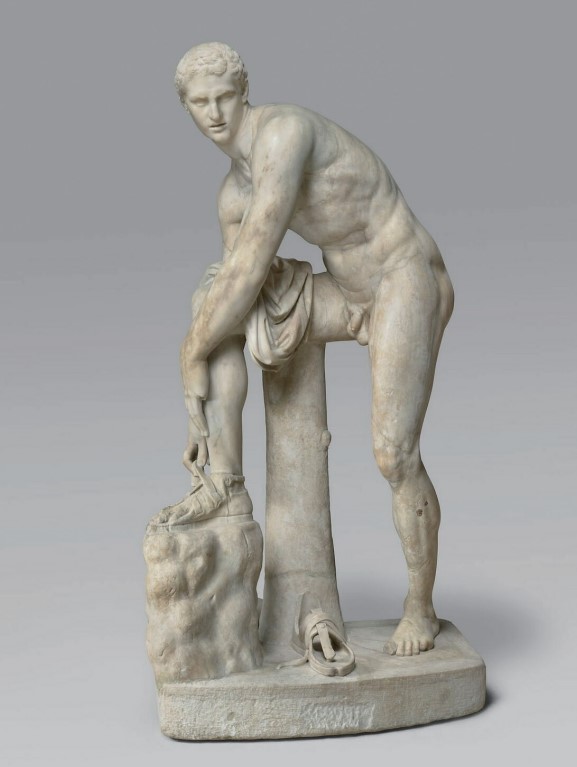

The "High Classical" period lasted only a few decades from about 450 to 400, but has had a momentous influence on art, and retains a special prestige, despite a very restricted number of original survivals. The best known works are the Parthenon Marbles, traditionally (since Plutarch) executed by a team led by the most famous ancient Greek sculptor Phidias, active from about 465–425, who was in his own day more famous for his colossal chryselephantine Statue of Zeus at Olympia (c. 432), one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, his Athena Parthenos (438), the cult image of the Parthenon, and Athena Promachos, a colossal bronze figure that stood next to the Parthenon; all of these are lost but are known from many representations. He is also credited as the creator of some life-size bronze statues known only from later copies whose identification is controversial, including the Ludovisi Hermes.

The High Classical style continued to develop realism and sophistication in the human figure, and improved the depiction of drapery (clothes), using it to add to the impact of active poses. Facial expressions were usually very restrained, even in combat scenes. The composition of groups of figures in reliefs and on pediments combined complexity and harmony in a way that had a permanent influence on Western art. Relief could be very high indeed, as in the Parthenon illustration below, where most of the leg of the warrior is completely detached from the background, as were the missing parts; relief this high made sculptures more subject to damage. The Late Classical style developed the free-standing female nude statue, supposedly an innovation of Praxiteles, and developed increasingly complex and subtle poses that were interesting when viewed from a number of angles, as well as more expressive faces; both trends were to be taken much further in the Hellenistic period.

The Pergamene style of

Hellenistic period

Small Greek terracotta figurines were very popular as ornaments in the home

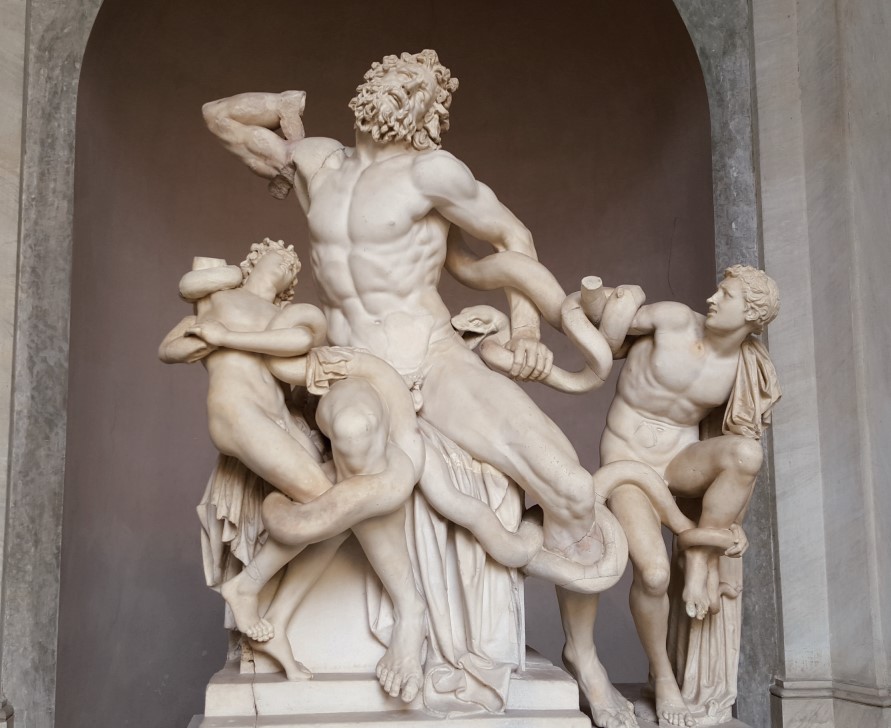

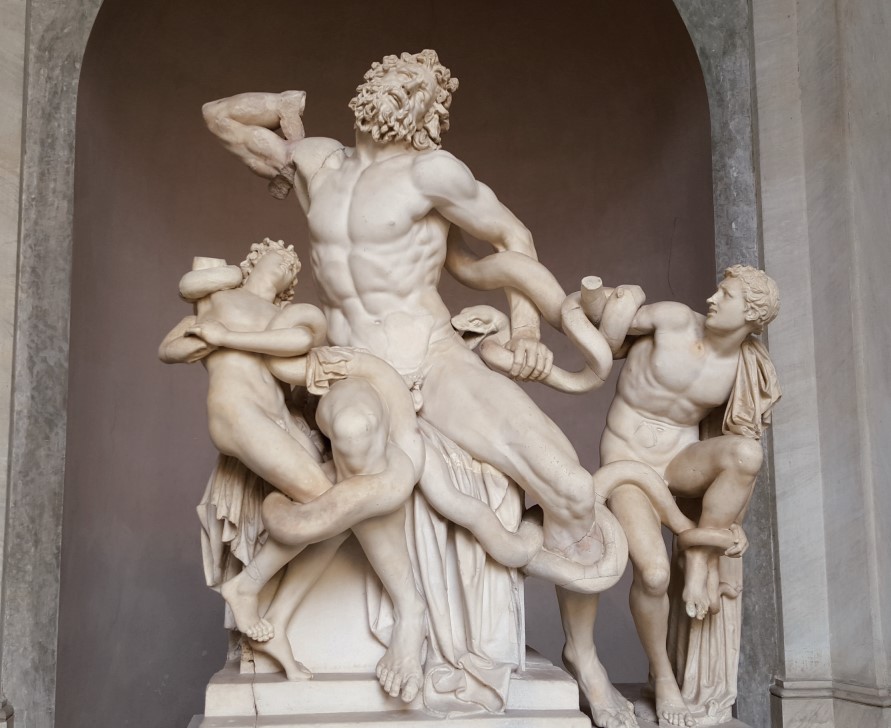

The Hellenistic period is conventionally dated from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, and ending either with the final conquest of the Greek heartlands by Rome in 146 BCE or with the final defeat of the last remaining successor-state to Alexander's empire after the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, which also marks the end of Republican Rome. It is thus much longer than the previous periods, and includes at least two major phases: a "Pergamene" style of experimentation, exuberance and some sentimentality and vulgarity, and in the 2nd century BCE a classicising return to a more austere simplicity and elegance; beyond such generalizations dating is typically very uncertain, especially when only later copies are known, as is usually the case. The initial Pergamene style was not especially associated with Pergamon, from which it takes its name, but the very wealthy kings of that state were among the first to collect and also copy Classical sculpture, and also commissioned much new work, including the famous Pergamon Altar whose sculpture is now mostly in Berlin and which exemplifies the new style, as do the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus (another of the Seven Wonders), the famous Laocoön and his Sons in the Vatican Museums, a late example, and the bronze original of The Dying Gaul (illustrated at top), which we know was part of a group actually commissioned for Pergamon in about 228 BCE, from which the Ludovisi Gaul was also a copy. The group called the Farnese Bull, possibly a 2nd-century marble original, is still larger and more complex,

The Pergamene style of the Hellenistic period, from the Pergamon Altar, early 2nd century

Hellenistic sculpture greatly expanded the range of subjects represented, partly as a result of greater general prosperity, and the emergence of a very wealthy class who had large houses decorated with sculpture, although we know that some examples of subjects that seem best suited to the home, such as children with animals, were in fact placed in temples or other public places. For a much more popular home decoration market there were Tanagra figurines, and those from other centres where small pottery figures were produced on an industrial scale, some religious but others showing animals and elegantly dressed ladies. Sculptors became more technically skilled in representing facial expressions conveying a wide variety of emotions and the portraiture of individuals, as well representing different ages and races. The reliefs from the Mausoleum are rather atypical in that respect; most work was free-standing, and group compositions with several figures to be seen in the round, like the Laocoon and the Pergamon group celebrating victory over the Gauls became popular, having been rare before. The Barberini Faun, showing a satyr sprawled asleep, presumably after drink, is an example of the moral relaxation of the period, and the readiness to create large and expensive sculptures of subjects that fall short of the heroic.

After the conquests of Alexander Hellenistic culture was dominant in the courts of most of the Near East, and some of Central Asia, and increasingly being adopted by European elites, especially in Italy, where Greek colonies initially controlled most of the South. Hellenistic art, and artists, spread very widely, and was especially influential in the expanding Roman Republic and when it encountered Buddhism in the easternmost extensions of the Hellenistic area. The massive so-called Alexander Sarcophagus found in Sidon in modern Lebanon, was probably made there at the start of the period by expatriate Greek artists for a Hellenized Persian governor. The wealth of the period led to a greatly increased production of luxury forms of small sculpture, including engraved gems and cameos, jewellery, and gold and silverware.

A native Italian style can be seen in the tomb monuments, which very often featured portrait busts, of prosperous middle-class Romans, and portraiture is arguably the main strength of Roman sculpture. There are no survivals from the tradition of masks of ancestors that were worn in processions at the funerals of the great families and otherwise displayed in the home, but many of the busts that survive must represent ancestral figures, perhaps from the large family tombs like the Tomb of the Scipios or the later mausolea outside the city.

The famous bronze head supposedly of Lucius Junius Brutus is very variously dated, but taken as a very rare survival of Italic style under the Republic, in the preferred medium of bronze. Similarly stern and forceful heads are seen on coins of the Late Republic, and in the Imperial period coins as well as busts sent around the Empire to be placed in the basilicas of provincial cities were the main visual form of imperial propaganda; even Londinium had a near-colossal statue of Nero, though far smaller than the 30-metre-high Colossus of Nero in Rome, now lost.

The Romans did not generally attempt to compete with free-standing Greek works of heroic exploits from history or mythology, but from early on produced historical works in relief, culminating in the great Roman triumphal columns with continuous narrative reliefs winding around them, of which those commemorating Trajan (CE 113) and Marcus Aurelius (by 193) survive in Rome, where the Ara Pacis ("Altar of Peace", 13 BCE) represents the official Greco-Roman style at its most classical and refined. Among other major examples are the earlier re-used reliefs on the Arch of Constantine and the base of the Column of Antoninus Pius (161), Campana reliefs were cheaper pottery versions of marble reliefs and the taste for relief was from the imperial period expanded to the sarcophagus. All forms of luxury small sculpture continued to be patronized, and quality could be extremely high, as in the silver Warren Cup, glass Lycurgus Cup, and large cameos like the Gemma Augustea, Gonzaga Cameo and the "Great Cameo of France". For a much wider section of the population, moulded relief decoration of pottery vessels and small figurines were produced in great quantity and often considerable quality.

After moving through a late 2nd-century "baroque" phase, in the 3rd century, Roman art largely abandoned, or simply became unable to produce, sculpture in the classical tradition, a change whose causes remain much discussed. Even the most important imperial monuments now showed stumpy, large-eyed figures in a harsh frontal style, in simple compositions emphasizing power at the expense of grace. The contrast is famously illustrated in the Arch of Constantine of 315 in Rome, which combines sections in the new style with roundels in the earlier full Greco-Roman style taken from elsewhere, and the Four Tetrarchs (c. 305) from the new capital of Constantinople, now in Venice. Ernst Kitzinger found in both monuments the same "stubby proportions, angular movements, an ordering of parts through symmetry and repetition and a rendering of features and drapery folds through incisions rather than modelling... The hallmark of the style wherever it appears consists of an emphatic hardness, heaviness and angularity—in short, an almost complete rejection of the classical tradition".

This revolution in style shortly preceded the period in which Christianity was adopted by the Roman state and the great majority of the people, leading to the end of large religious sculpture, with large statues now only used for emperors. However, rich Christians continued to commission reliefs for sarcophagi, as in the Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, and very small sculpture, especially in ivory, was continued by Christians, building on the style of the consular diptych.

next period is

Early Medieval and Byzantine

The Early Christians were opposed to monumental religious sculpture, though Roman traditions continued in portrait busts and sarcophagus reliefs, as well as smaller objects such as the consular diptych. Such objects, often in valuable materials, were also the main sculptural traditions (as far as is known) of the civilizations of the Migration period, as seen in the objects found in the 6th-century burial treasure at Sutton Hoo, and the jewellery of Scythian art and the hybrid Christian and animal style productions of Insular art. Following the continuing Byzantine tradition, Carolingian art revived ivory carving in the West, often in panels for the treasure bindings of grand illuminated manuscripts, as well as crozier heads and other small fittings.

The Gero Cross, c. 965–970, Cologne, Germany, the first great example of the revival of large sculpture

Byzantine art, though producing superb ivory reliefs and architectural decorative carving, never returned to monumental sculpture, or even much small sculpture in the round. However, in the West during the Carolingian and Ottonian periods there was the beginnings of a production of monumental statues, in courts and major churches. This gradually spread; by the late 10th and 11th century there are records of several apparently life-size sculptures in Anglo-Saxon churches, probably of precious metal around a wooden frame, like the Golden Madonna of Essen. No Anglo-Saxon example has survived, and survivals of large non-architectural sculpture from before the year 1000 are exceptionally rare. Much the finest is the Gero Cross, of 965–970, which is a crucifix, which was evidently the commonest type of sculpture; Charlemagne had set one up in the Palatine Chapel in Aachen around 800. These continued to grow in popularity, especially in Germany and Italy. The runestones of the Nordic world, the Pictish stones of Scotland and possibly the high cross reliefs of Christian Great Britain, were northern sculptural traditions that bridged the period of Christianization.

The Pergamene style of

Romanesque

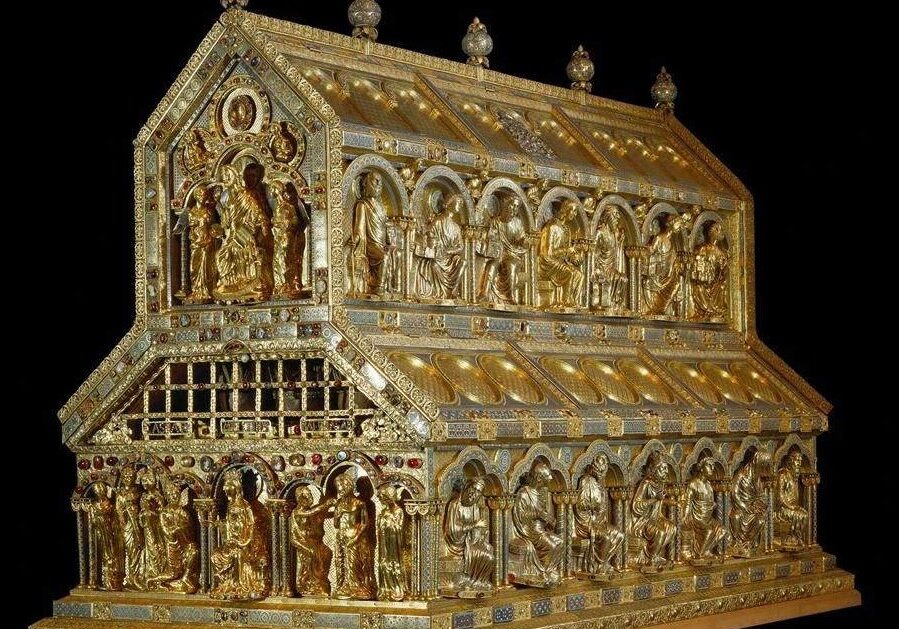

Shrine of the Three Kings in Cologne Cathedral

Beginning in roughly 1000 A.D., there was a rebirth of artistic production in all Europe, led by general economic growth in production and commerce, and the new style of Romanesque art was the first medieval style to be used in the whole of Western Europe. The new cathedrals and pilgrim's churches were increasingly decorated with architectural stone reliefs, and new focuses for sculpture developed, such as the tympanum over church doors in the 12th century, and the inhabited capital with figures and often narrative scenes. Outstanding abbey churches with sculpture include in France Vézelay and Moissac and in Spain Silos.

Romanesque art was characterised by a very vigorous style in both sculpture and painting. The capitals of columns were never more exciting than in this period, when they were often carved with complete scenes with several figures. The large wooden crucifix was a German innovation right at the start of the period, as were free-standing statues of the enthroned Madonna, but the high relief was above all the sculptural mode of the period. Compositions usually had little depth, and needed to be flexible to squeeze themselves into the shapes of capitals, and church typanums; the tension between a tightly enclosing frame, from which the composition sometimes escapes, is a recurrent theme in Romanesque art. Figures still often varied in size in relation to their importance portraiture hardly existed.

Objects in precious materials such as ivory and metal had a very high status in the period, much more so than monumental sculpture — we know the names of more makers of these than painters, illuminators or architect-masons. Metalwork, including decoration in enamel, became very sophisticated, and many spectacular shrines made to hold relics have survived, of which the best known is the Shrine of the Three Kings at Cologne Cathedral by Nicholas of Verdun. The bronze Gloucester candlestick and the brass font of 1108–17 now in Liège are superb examples, very different in style, of metal casting, the former highly intricate and energetic, drawing on manuscript painting, while the font shows the Mosan style at its most classical and majestic.

The bronze doors, a triumphal column and other fittings at Hildesheim Cathedral, the Gniezno Doors, and the doors of the Basilica di San Zeno in Verona are other substantial survivals. The aquamanile, a container for water to wash with, appears to have been introduced to Europe in the 11th century, and often took fantastic zoomorphic forms; surviving examples are mostly in brass. Many wax impressions from impressive seals survive on charters and documents, although Romanesque coins are generally not of great aesthetic interest.

The Cloisters Cross is an unusually large ivory crucifix, with complex carving including many figures of prophets and others, which has been attributed to one of the relatively few artists whose name is known, Master Hugo, who also illuminated manuscripts. Like many pieces it was originally partly coloured. The Lewis chessmen are well-preserved examples of small ivories, of which many pieces or fragments remain from croziers, plaques, pectoral crosses and similar objects.

In Italy Nicola Pisano (1258–1278) and his son Giovanni developed a style that is often called Proto-Renaissance, with unmistakable influence from Roman sarcophagi and sophisticated and crowded compositions, including a sympathetic handling of nudity, in relief panels on their Siena Cathedral Pulpit (1265–68), Pulpit in the Pisa Baptistery (1260), the Fontana Maggiore in Perugia, and Giovanni's pulpit in Pistoia of 1301. Another revival of classical style is seen in the International Gothic work of Claus Sluter and his followers in Burgundy and Flanders around 1400. Late Gothic sculpture continued in the North, with a fashion for very large wooden sculpted altarpieces with increasingly virtuoso carving and large numbers agitated expressive figures; most surviving examples are in Germany, after much iconoclasm elsewhere. Tilman Riemenschneider, Veit Stoss and others continued the style well into the 16th century, gradually absorbing Italian Renaissance influences.

Life-size tomb effigies in stone or alabaster became popular for the wealthy, and grand multi-level tombs evolved, with the Scaliger Tombs of Verona so large they had to be moved outside the church. By the 15th century there was an industry exporting Nottingham alabaster altar reliefs in groups of panels over much of Europe for economical parishes who could not afford stone retables. Small carvings, for a mainly lay and often female market, became a considerable industry in Paris and some other centres. Types of ivories included small devotional polyptychs, single figures, especially of the Virgin, mirror-cases, combs, and elaborate caskets with scenes from Romances, used as engagement presents. The very wealthy collected extravagantly elaborate jewelled and enamelled metalwork, both secular and religious, like the Duc de Berry's Holy Thorn Reliquary, until they ran short of money, when they were melted down again for cash.

The period was marked by a great increase in patronage of sculpture by the state for public art and by the wealthy for their homes; especially in Italy, public sculpture remains a crucial element in the appearance of historic city centres. Church sculpture mostly moved inside just as outside public monuments became common. Portrait sculpture, usually in busts, became popular in Italy around 1450, with the Neapolitan Francesco Laurana specializing in young women in meditative poses, while Antonio Rossellino and others more often depicted knobbly-faced men of affairs, but also young children. The portrait medal invented by Pisanello also often depicted women; relief plaquettes were another new small form of sculpture in cast metal.

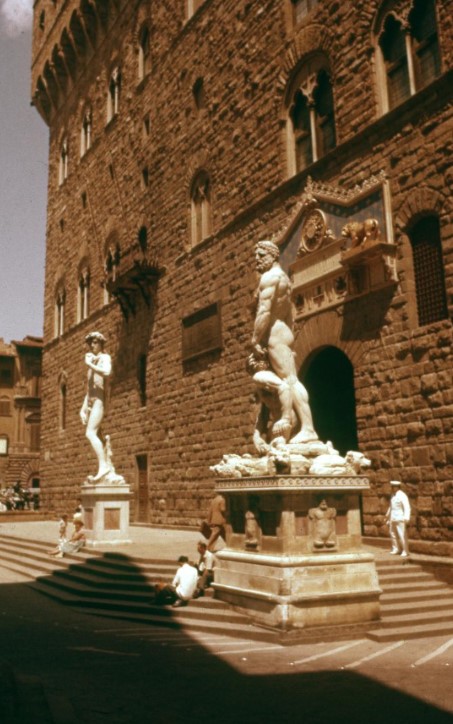

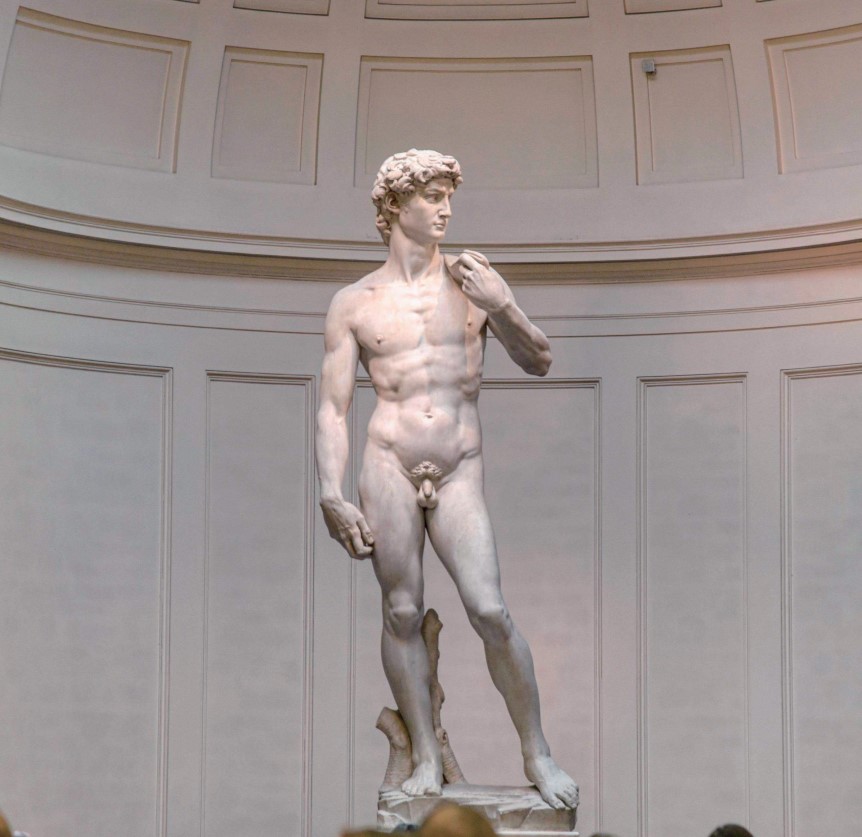

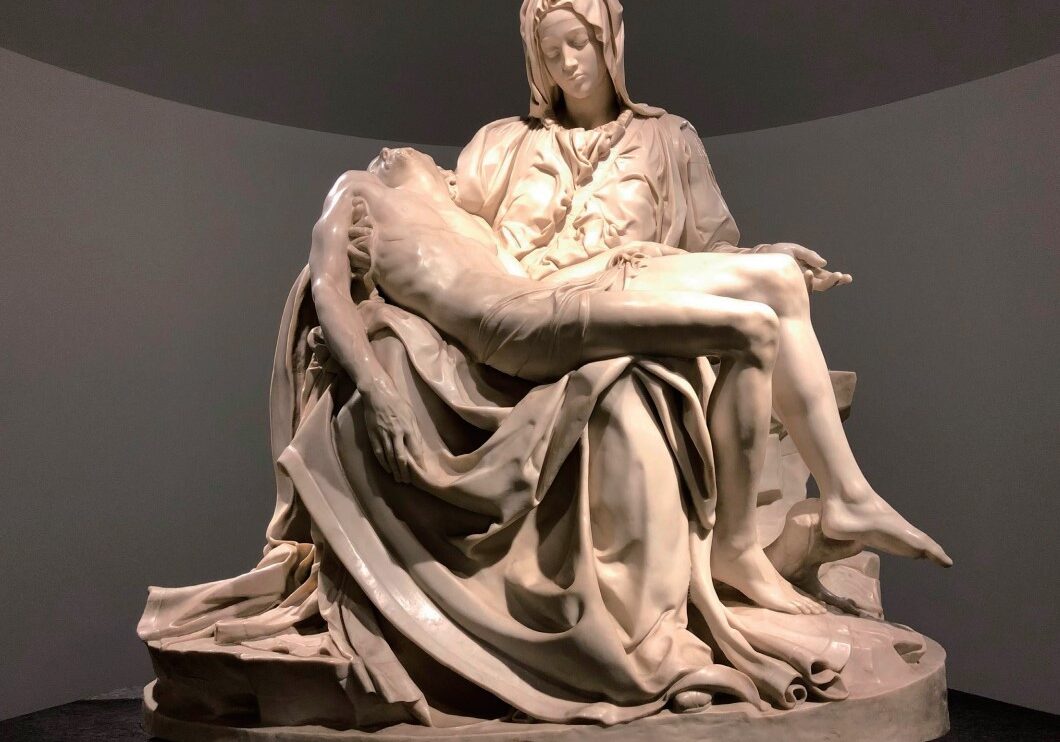

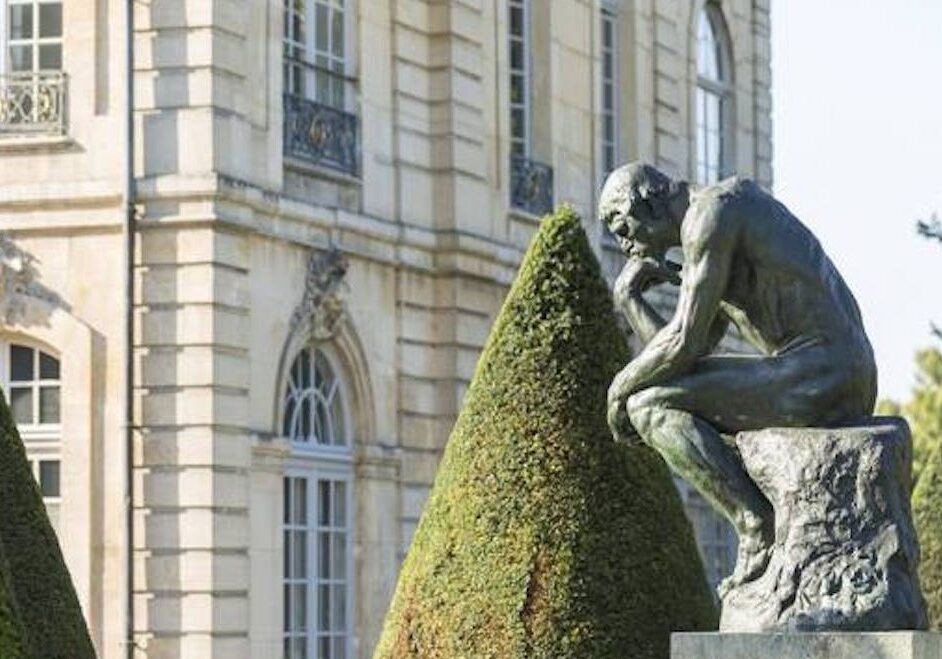

Michelangelo was an active sculptor from about 1500 to 1520, and his great masterpieces including his David, Pietà, Moses, and pieces for the Tomb of Pope Julius II and Medici Chapel could not be ignored by subsequent sculptors. His iconic David (1504) has a contrapposto pose, borrowed from classical sculpture. It differs from previous representations of the subject in that David is depicted before his battle with Goliath and not after the giant's defeat. Instead of being shown victorious, as Donatello and Verocchio had done, David looks tense and battle ready.

Like other works of his, and other Mannerists, it removes far more of the original block than Michelangelo would have done. Cellini's bronze Perseus with the head of Medusa is certainly a masterpiece, designed with eight angles of view, another Mannerist characteristic, but is indeed mannered compared to the Davids of Michelangelo and Donatello. Originally a goldsmith, his famous gold and enamel Salt Cellar (1543) was his first sculpture, and shows his talent at its best.] As these examples show, the period extended the range of secular subjects for large works beyond portraits, with mythological figures especially favoured; previously these had mostly been found in small works.

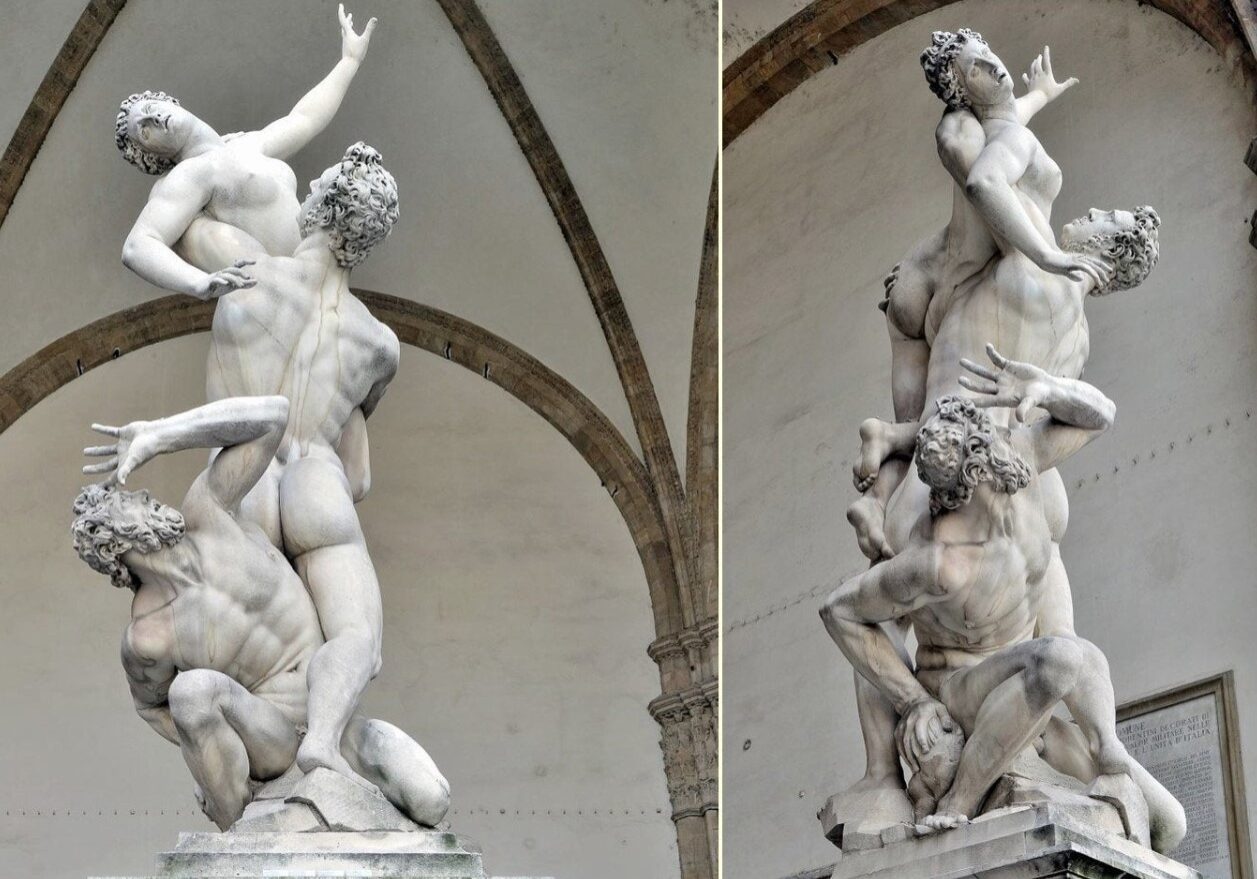

Small bronze figures for collector's cabinets, often mythological subjects with nudes, were a popular Renaissance form at which Giambologna, originally Flemish but based in Florence, excelled in the later part of the century, also creating life-size sculptures, of which two joined the collection in the Piazza della Signoria. He and his followers devised elegant elongated examples of the figura serpentinata, often of two intertwined figures, that were interesting from all angles.

The Baroque style was perfectly suited to sculpture, with Gian Lorenzo Bernini the dominating figure of the age in works such as The Ecstasy of St Theresa (1647–1652). Much Baroque sculpture added extra-sculptural elements, for example, concealed lighting, or water fountains, or fused sculpture and architecture to create a transformative experience for the viewer. Artists saw themselves as in the classical tradition, but admired Hellenistic and later Roman sculpture, rather than that of the more "Classical" periods as they are seen today.

The Protestant Reformation brought an almost total stop to religious sculpture in much of Northern Europe, and though secular sculpture, especially for portrait busts and tomb monuments, continued, the Dutch Golden Age has no significant sculptural component outside goldsmithing. Partly in direct reaction, sculpture was as prominent in Roman Catholicism as in the late Middle Ages. Statues of rulers and the nobility became increasingly popular. In the 18th century much sculpture continued on Baroque lines—the Trevi Fountain was only completed in 1762. Rococo style was better suited to smaller works, and arguably found its ideal sculptural form in early European porcelain, and interior decorative schemes in wood or plaster such as those in French domestic interiors and Austrian and Bavarian pilgrimage churches.