aRT museum Collection

We've selected specific masterpieces by many renowed historical artists and sculptures. Giving the Art museum another layer of rich artistry and history. Feast your eyes on some of the most renowned sculptures around the world and learn their origin and history.

Enjoy the experience of each unique artistry. You'll also get to learn the history and origin behind each individual sculpture. Making your experience even more fascinating and interesting.

Winged Victory of Samothrace

Louvre Museum

From a hillside overlook, Winged Victory originally presided over a temple complex to which pilgrims from across the region thronged between the fourth and second centuries BCE to undergo initiation in the secret rites of a mystery religious cult. The rites, being secret, remain so, but are thought to have involved blindfolds, torchlit processions, and bountiful libations.

Dating to ca. 190 BCE, the statue depicts the goddess Victory, or Nike, alighting on the prow of a warship. Although Winged Victory is widely believed to have been sculpted to commemorate a naval victory, neither the battle nor the sculptor has been determined.

Ten million visitors a year gape at the majesty of Winged Victory of Samothrace in the Louvre, where she appears ready to take flight from her perch atop the Daru staircase. The eight-foot marble statue was installed in Paris shortly after its discovery on the remote Greek island of Samothrace in 1863 by French diplomat and amateur archaeologist Charles Champoiseau.

Statue of David

Academy of Fine arts of Florence

Better than anyone else, Giorgio Vasari introduces in a few words the marvel of one of the greatest masterpieces ever created by mankind. At the Accademia Gallery, you can admire from a short distance the perfection of the most famous statue in Florence and, perhaps, in all the world: Michelangelo’s David.

This astonishing Renaissance sculpture was created between 1501 and 1504. It is a 14.0 ft marble statue depicting the Biblical hero David, represented as a standing male nude. Originally commissioned by the Opera del Duomo for the Cathedral of Florence, it was meant to be one of a series of large statues to be positioned in the niches of the cathedral’s tribunes, way up at about 80mt from the ground. Michelangelo Buonarroti was asked by the consuls of the Board to complete an unfinished project begun in 1464 by Agostino di Duccio and later carried on by Antonio Rossellino in 1475. Both sculptors had in the end rejected an enormous block of marble due to the presence of too many “taroli”, or imperfections, which may have threatened the stability of such a huge statue. This block of marble of exceptional dimensions remained therefore neglected for 25 years, lying within the courtyard of the Opera del Duomo (Vestry Board).

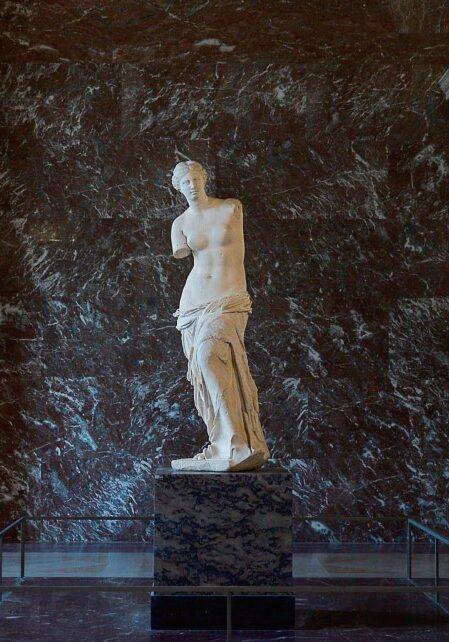

The Venus de Milo

Louvre Museum

The Venus de Milo, also known as Aphrodite of Melos, is an iconic ancient Greek marble sculpture, believed to be a representation of the goddess Aphrodite, found on the island of Melos (Milos) in 1820 and now displayed at the Louvre Museum in Paris.

The Venus de Milo is believed to depict Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love, whose Roman counterpart was Venus. Made of Parian marble, the statue is larger than life size, standing over 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) high. The statue of the goddess was found on the Aegean island of Milos, to which she owes her name, on the eve of the Greek War of Independence (1821-1830 CE). That's why it's called Venus de Milo not Venus de Aphrodite.

The Venus de Milo can be admired today in the last of a long series of rooms where she stands in almost solitary splendour. The magnificent red marble decoration dates from the early 19th century and the reign of Napoleon I.

The statue is the creation of an artist named Alexandros of Antioch.

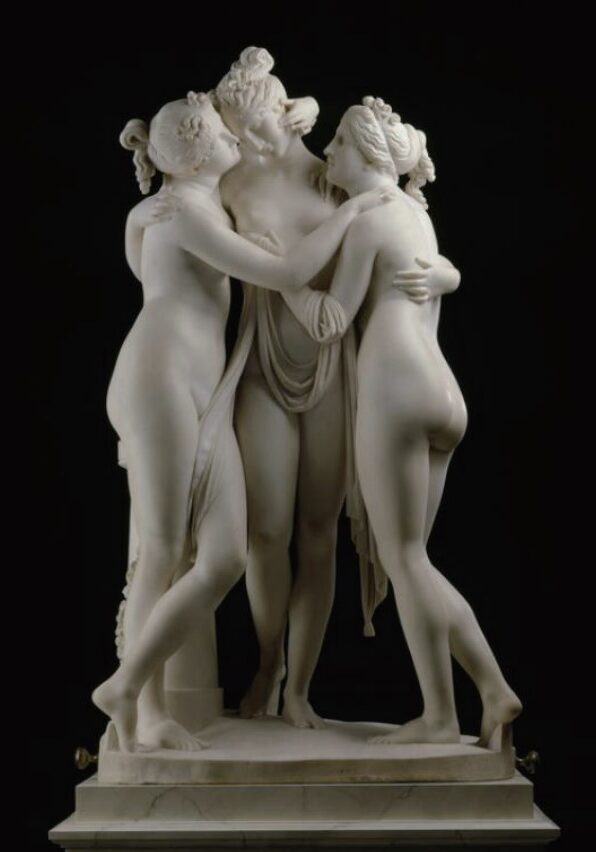

The three graces

by Antonio Canova

The State Hermitage Museum

Regarded internationally as a masterpiece of neoclassical European sculpture, The Three Graces was carved in Rome by Antonio Canova (1757 – 1822) between 1814 and 1817 for an English collector. This group of three mythological sisters was in fact a second version of an original – one commissioned by Joséphine de Beauharnais, first wife of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Taking its motif from ancient Greek literature, The Three Graces depicts the three daughters of Zeus, each of whom is described as being able to bestow a particular gift on humanity: (from left to right) Euphrosyne (mirth), Aglaia (elegance) and Thalia (youth and beauty). The first version of this piece was commissioned by one of the era's most famous women, Joséphine de Beauharnais, who was by then the divorced first wife of Napoleon. In May 1814, before Antonio Canova had completed the sculpture, De Beauharnais died. John Russell, the 6th Duke of Bedford, visited Canova's studio in Rome in December that year and, impressed by the artistry of The Three Graces, told Canova he wanted to acquire the finished marble. De Beauharnais' son, Prince Eugène de Beauharnais, also wanted to buy the group his mother had commissioned, so Canova offered to make the Duke of Bedford a 'replica with alterations'.

Soon after he accepted this offer, in January 1815, the Duke wrote to the artist saying,

"I frankly declare that I have seen nothing in ancient or modern sculpture that has given me more pleasure … I leave the variations in the group … entirely to your judgement, but I hope that the true grace that so particularly distinguishes this work will be completely preserved."

Psyche Revived by Cupid's Kiss

by Antonio Canova

lOUVRE mUSEUM

Psyche was a beautiful princess. So beautiful that Venus, the goddess of beauty, was furiously jealous of her. She ordered her son, Cupid, to punish the young girl. But Cupid fell in love with Psyche and carried her off to an enchanted castle. Everything seemed to be going so well for the couple, but Psyche broke a promise she made to Cupid and the god fled. Venus then gave Psyche a series of impossible missions to carry out, including going to the underworld and bringing back a beauty potion. Psyche managed to do it, but when she opened the bottle to take a sniff, she fell down lifeless. Fortunately, Cupid brought her back to life with a kiss. This is the moment Canova chose to depict. Adriaen de Vries, a Renaissance sculptor also inspired by this myth, chose to show what happened next. On the order of Jupiter, Mercury – the messenger of the gods – carried off Psyche (who is still holding the beauty potion in her hand) to the heavens where she was granted immortality. Through this story, the sculptor symbolically represents art, embodied by Mercury, which elevates the soul, ‘psyche’ in Greek, to an immortal state.

tHE THREE GRACES

lOUVRE mUSEUM

Marble statue of the Three Graces dancing in a circle. 2nd century CE Roman copy of a Greek statue of the 2nd century BCE with Rennaisance era restorations. Found in the Villa Cornovaglia in Rome. Louvre Museum, Paris.

The Graces of Greek mythology, also called the Charites, are sister goddesses of beauty, grace, and charm. In Roman mythology, the Graces are called the Gratiae. Their names are Aglaea, which means radiance or beauty; Euphrosyne, which means joy; and Thalia, which means bloom.

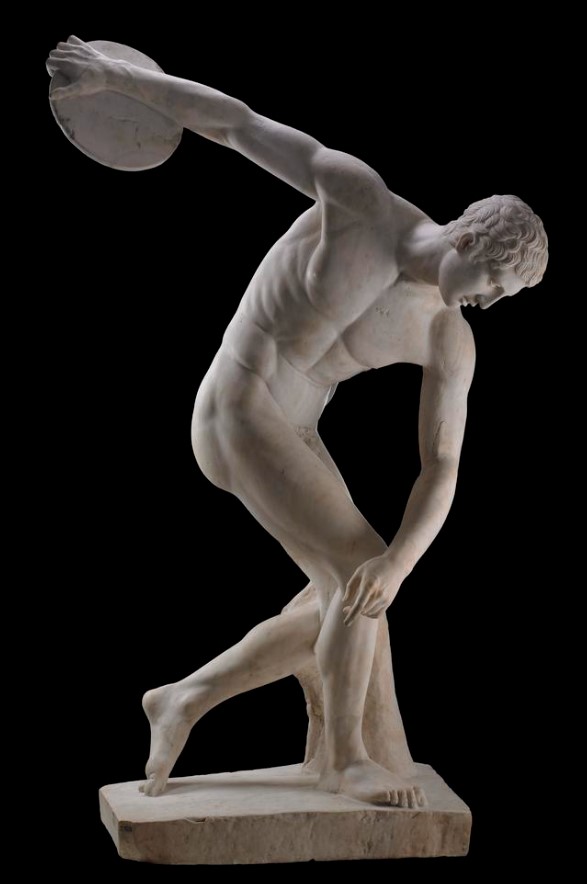

The Townley Diskobolos

by myron

National Museum of Rome. Palazzo Massimo.

Marble statue of a diskobolos (or discobolus), discus thrower, poised as if ready to throw his discus.

This particular copy has an incorrectly restored head, that was allegedly found nearby when it was excavated in Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli. It was common in the eighteenth century to “restore” ancient sculptures without proof that the restored elements actually belonged together: clients and collctors generally desired completeness rather than authenticity. That the original bronze athlete by Myron had its head turned to look back at the discus, rather than being lowered, is demonstrated by other versions of the statue that were discovered with their heads unbroken from the body.

Restored: nose, lips, chin, part of discus and right hand, section of neck, left hand, part of right knee and parts of toes.

Diane de Versailles

lOUVRE mUSEUM

Diana, the Roman equivalent of the Greek goddess Artemis, tirelessly springs forward, while taking an arrow from the quiver on her right shoulder. A deer jumps at her left. She wears a short chiton (tunic) to make her movements easier.

The sculpture resembles that of her brother, the Apollo Belvedere. However there is little evidence that the two works are by the same sculptor, as has been claimed.

Diana is represented at the hunt, hastening forward, as if in pursuit of game. She looks toward the right and with raised right arm is about to draw an arrow from her quiver. Her left arm has been restored, and a deer has been added at her feet, although one might have expected a dog. Her left hand is holding a small cylindrical fragment, which may be part of what was once a bow. She wears a short Dorian chiton, a himation around her waist, and sandals. Her second toes are longer than her big toes, a condition known as Morton's toe

The date has been disputed: it is now thought that the bronze original dated to around 100 BCE rather than to the fourth century BCE. Either way, this is a Roman copy

Apollo and Daphne

by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

Galleria Borghese in Rome

Bernini depicts the mythological drama that occurs between Apollo, god of music and poetry, and Daphne, a virginal nymph. The artist was likely inspired by the classical sculpture Apollo Belvedere (circa 2nd century CE) as well as the ancient Roman poet Ovid’s rendition of the myth. In Ovid’s telling, the story begins with a contest between two male gods: After Apollo insults Eros (or Cupid), Eros takes revenge by orchestrating a scene of unrequited passion and possession. He shoots a golden arrow into Apollo, which makes him fall desperately in love with Daphne, then embeds a leaden arrow in her, enhancing the repulsion she feels towards her pursuer.

Daphne flees Apollo’s hungry advances. When he catches up to her, she sacrifices her human body and assumes the form of a laurel tree. Even then, as Ovid explains, Apollo doesn’t let up: “[He] loved her still. He placed his hand where he had hoped and felt the heart still beating.

Under the bark and he embraced the branches, as if they were still limbs, and kissed the wood.” Daphne, however, still resisted: “And the wood shrank from his kisses.”

When famed Baroque sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini unveiled Apollo and Daphne in 1625, the marble work was resoundingly hailed as a meraviglia—a marvel. Not yet 30 years old, the sculptor had captured motion, transformation, sexual appetite, and terror more convincingly than any other artist working in stone before him. “Immediately when it was...finished, there arose such a cry that all Rome concurred in seeing it as a miracle,” art historian Filippo Baldinucci recalled of the masterpiece’s public debut, in his 1682 biography, Life of Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

Almost 400 years later, Apollo and Daphne remains mesmerizing for both its formal mastery and its disturbing, profoundly relevant subject matter: the ravenous pursuit of a woman, by a man who won’t take no for an answer.

L'Amour et Psyché debout

by Antonio Canova

lOUVRE mUSEUM

This sculptural group represents the famous couple from Greek mythology. The myth tells that the extraordinary beauty of a young girl named Psyche aroused the envy of Venus herself, so much so that the goddess sent her son Cupid to make her fall in love with a very ugly man. However, the young god himself fell in love with the beautiful girl. Thus began a tormented love affair that, after being long hindered by Venus and punctuated by a thousand trials, lasted forever.

Canova depicted the figures of Cupid and Psyche several times, but in this sculpture, he depicts them standing. Psyche offers Cupid a butterfly, a symbol of his own soul.

A veiled Vestal Virgin

by Raffaele Monti

Chatsworth House

In Ancient Rome, the Vestals were virgin priestesses whose lives were dedicated to the goddess Vesta. They were tasked to look after the sacred fire burning on her altar in the temple of Vesta, and were regarded as fundamental to the safety of Rome. The discovery of a "House of the Vestals" in Pompeii in the 18th century made Vestals a popular subject matter in art over the following 50 years.

The 6th Duke of Devonshire visited the sculptor's studio in Milan, Italy, on 12 October 1846 on his way to Naples. He ordered the marble sculpture on 18 October, placing a £60 deposit on the following day. The sculpture was ready to be dispatched to England in April 1847, and the Duke appears to have displayed it in Chiswick House, west of London.

It first came to Chatsworth in 1999 and was shown in the Sculpture Gallery where it appeared in the 2005 film 'Pride and Prejudice', starring Keira Knightley and Matthew Macfadyen.